Entamoeba histolytica

|

Entamoeba

histolytica |

|

|

Entamoeba

histolytica trophozoite |

|

|

Domain: |

|

|

Phylum: |

|

|

Family: |

|

|

Genus: |

|

|

Species: |

E. histolytica |

|

Entamoeba

histolytica |

|

.0.0

Entamoeba

histolytica is an anaerobic parasitic amoebozoan, part of

the genus Entamoeba. Predominantly

infecting humans and other primates causing amoebiasis, E.

histolytica is estimated to infect about 35-50 million people

worldwide. E.histolytica infection

is estimated to kill more than 55,000 people each year. Previously, it was

thought that 10% of the world population was infected, but these figures

predate the recognition that at least 90% of these infections were due to a

second species, E. dispar. Mammals such as dogs and cats

can become infected transiently but are not thought to contribute significantly

to transmission.

The word histolysis literally

means disintegration and dissolution of organic tissues.

Transmission

The active (trophozoite) stage exists

only in the host and in fresh loose feces; cysts survive

outside the host in water, in soils, and on foods, especially under moist

conditions on the latter. The infection can occur when a person puts anything

into their mouth that has touched the feces of a person who is infected

with E. histolytica, swallows something, such as water or food,

that is contaminated with E. histolytica, or swallows E.

histolytica cysts (eggs) picked up from contaminated surfaces or

fingers. The cysts

are readily killed by heat and by freezing temperatures; they survive for only

a few months outside of the host.[5] When cysts

are swallowed, they cause infections by excysting (releasing the trophozoite

stage) in the digestive tract. The pathogenic nature of E. histolytica was

first reported by Fedor A. Lösch in 1875, but it was

not given its Latin name until Fritz Schaudinn described

it in 1903. E. histolytica, as its name suggests (histo–lytic =

tissue destroying), is pathogenic; infection can

be asymptomatic, or it can lead to amoebic

dysentery or amoebic liver abscess. Symptoms

can include fulminating dysentery, bloody diarrhea, weight loss, fatigue,

abdominal pain, and amoeboma. The amoeba can

'bore' into the intestinal wall, causing lesions and intestinal symptoms, and

it may reach the blood stream. From there, it can reach vital organs of the

human body, usually the liver, but sometimes the lungs, brain, and spleen. A

common outcome of this invasion of tissues is a liver abscess, which can be

fatal if untreated. Ingested red blood cells are

sometimes seen in the amoeba cell cytoplasm.

Risk factors

Poor sanitary

conditions are known to increase the risk of contracting amebiasis E.

histolytica.

In the United States, there is a much higher rate

of amebiasis-related mortality in California and Texas (this might be caused by

the proximity of those states to E. histolytica-endemic areas, such

as Mexico), parts of Latin America, and Asia. E.

histolytica is also recognized as an emerging sexually transmissible

pathogen, especially in male homosexual relations, causing outbreaks in

non-endemic regions. As such, high-risk sex

behavior is also a potential source of infection. Although it

is unclear whether there is a causal link, studies indicate a higher chance of

being infected with E. histolytica if one is also infected

with HIV.

Genome

The E.

histolytica genome was

sequenced, assembled, and automatically annotated in 2005. The genome

was reassembled and reannotated in 2010.[15] The 20

million basepair genome assembly contains 8,160 predicted genes known and

novel transposable elements have been

mapped and characterized, functional assignments have been revised and updated,

and additional information has been incorporated, including metabolic

pathways, Gene Ontology assignments,

curation of transporters, and generation of gene families.[16] The major

group of transposable elements in E. histolytica are non-LTR

retrotransposons. These have been divided in three families called EhLINEs and

EhSINEs (EhLINE1,2,3 and EhSINE1,2,3). EhLINE1 encode an endonuclease

(EN) protein (in addition to reverse transcriptase and nucleotide-binding

ORF1), which have similarity with bacterial restriction endonuclease. This similarity with bacterial

protein indicates that transposable

elements have been acquired from prokaryotes by horizontal gene transfer in this

protozoan parasite.

The genome

of E. histolytica has been found to have snoRNAs with opisthokont-like features. The E. histolytica U3 snoRNA

(Eh_U3 snoRNA) has showed sequence and structural features similar to Homo

sapiens U3 snoRNA.

Pathogen interaction

E. histolytica may

modulate the virulence of certain human viruses and is itself a host for its

own viruses.

For example, AIDS

accentuates the damage and pathogenicity of E. histolytica.[13] On the

other hand, cells infected with HIV are often consumed by E.

histolytica. Infective HIV remains viable within the amoeba, although there

has been no proof of human reinfection from amoeba carrying this virus.

A burst of

research on viruses of E. histolytica stems from a series of

papers published by Diamond et al. from 1972 to 1979. In 1972,

they hypothesized two separate polyhedral and filamentous viral strains

within E. histolytica that caused cell lysis. Perhaps the most

novel observation was that two kinds of viral strains existed, and that within

one type of amoeba (strain HB-301) the polyhedral strain had no detrimental

effect but led to cell lysis in another (strain HK-9). Although Mattern et al.

attempted to explore the possibility that these protozoal viruses could

function like bacteriophages, they found no significant changes in Entamoeba

histolytica virulence when infected by viruses.

Immunopathogenesis

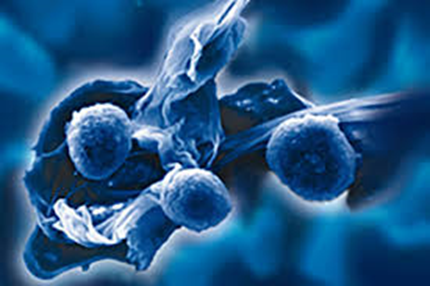

E. histolytica causes

tissue destruction which leads to clinical disease. E. histolytica–induced

tissue damage by three main events: direct host cell death, inflammation, and

parasite invasion. Once the trophozoites are excysted in the terminal ileum

region, they colonize the large bowel, remaining on the surface of the mucus

layer and feeding on bacteria and food particles. Occasionally, and in response

to unknown stimuli, trophozoites move through the mucus layer where they come

in contact with the epithelial cell layer and start the pathological

process. E. histolytica has a lectin that binds

to galactose and N-acetylgalactosamine sugars on the surface of the epithelial

cells, The lectin normally is used to bind bacteria for ingestion. The parasite

has several enzymes such as pore forming proteins, lipases, and cysteine

proteases, which are normally used to digest bacteria in food vacuoles but

which can cause lysis of the epithelial cells by inducing cellular necrosis and

apoptosis when the trophozoite comes in contact with them and binds via the

lectin. Enzymes released allow penetration into intestinal wall and blood

vessels, sometimes on to liver and other organs. The trophozoites will then

ingest these dead cells. This damage to the epithelial cell layer attracts

human immune cells and these in turn can be lysed by the trophozoite, which

releases the immune cell's own lytic enzymes into the surrounding tissue,

creating a type of chain reaction and leading to tissue destruction. This

destruction manifests itself in the form of an 'ulcer' in the tissue, typically

described as flask-shaped because of its appearance in transverse section. This

tissue destruction can also involve blood vessels leading to bloody diarrhea,

amebic dysentery. Occasionally, trophozoites enter the bloodstream where they

are transported typically to the liver via the portal system. In the liver a

similar pathological sequence ensues, leading to amebic liver abscesses. The

trophozoites can also end up in other organs, sometimes via the bloodstream,

sometimes via liver abscess rupture or fistulas. Similarly, when

the trophozoites travel to the brain, they can cause amoebic brain abscess.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is

confirmed by microscopic examination for trophozoites or cysts in fresh or

suitably preserved faecal specimens, smears of aspirates or scrapings obtained

by proctoscopy, and aspirates of abscesses or other tissue specimen. A blood

test is also available, but it is recommended only when a healthcare provider

believes the infection may have spread beyond the intestine to some other organ

of the body, such as the liver. However, this blood test may not be helpful in

diagnosing current illness, because the test can be positive if the patient has

had amebiasis in the past, even if they are not infected at the time of the

test.[24] Stool

antigen detection and PCR are available for diagnosis, and are more sensitive

and specific than microscopy.

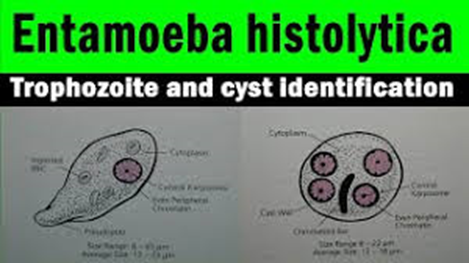

Entamoeba histolytica trophozoite

Amoebic intestinal ulcer caused by E.

histolytica

Trophozoites of E.

histolytica with ingested erythrocytes

E. histolytica cyst

Immature E. histolytica cyst (mature

cysts have 4 nuclei)

E. histolytica quadrinucleate cyst with

chromatoid bodies.

Multiplication by binary fission

E. histolytica drawing

Immunohistochemical staining of trophozoites (brown)

using specific anti–Entamoeba histolytica macrophage migration

inhibitory factor antibodies in a patient with amebic colitis.

Treatment

There are a

number of effective medications. Several antibiotics are available to

treat Entamoeba histolytica. The infected individual will be

treated with only one antibiotic if the E. histolytica infection

has not made the person sick, and will most likely be prescribed two

antibiotics if the person has been feeling sick. Otherwise, below are

other options for treatments.

Intestinal

Usually nitroimidazole derivatives

(such as metronidazole) are used, because they are highly effective against the

trophozoite form of the amoeba. Since they have little effect on amoeba cysts, usually this

treatment is followed by an agent (such as paromomycin or diloxanide furoate)

that acts on the organism in the lumen.

Liver abscess:

In addition to

targeting organisms in solid tissue, primarily with drugs like metronidazole and chloroquine, treatment of

liver abscess must include agents that act in the lumen of the intestine (as in

the preceding paragraph) to avoid re-invasion. Surgical drainage is usually not

necessary, except when rupture is imminent.

People without

symptoms: For people without symptoms (otherwise known as asymptomatic

carriers), non-endemic areas should be treated by paromomycin; other

treatments include diloxanide

furoate, and iodoquinol. There have been problems with the use of

iodoquinol and iodochlorhydroxyquin, so their use is not recommended.

Diloxanide furoate can also be used by mildly symptomatic persons who are just

passing cysts.

|

Genus

and |

Entamoeba

histolytica |

|

Etiologic

agent of: |

Amoebiasis; amoebic

dysentery;

extraintestinal amoebiasis, usually amoebic liver abscess; "anchovy

sauce"); amoeba cutis; amoebic lung abscess ("liver-colored

sputum") |

|

Infective

stage |

Tetranucleated

cyst (having 2–4 nuclei) |

|

Definitive

host |

Human |

|

Portal

of entry |

Mouth |

|

Mode

of transmission |

Ingestion

of mature cyst through contaminated food or water |

|

Habitat |

Colon

and cecum |

|

Pathogenic

stage |

|

|

Locomotive

apparatus |

Pseudopodia

("false foot”") |

|

Motility |

Active,

progressive and directional |

|

Nucleus |

'Ring

and dot' appearance: peripheral chromatin and central karyosome |

|

Mode

of reproduction |

Binary

fission |

|

Pathogenesis |

Lytic

necrosis (it looks like “flask-shaped” holes in Gastrointestinal tract

sections (GIT) |

|

Type

of encystment |

Protective

and Reproductive |

|

Lab

diagnosis |

Most

common is direct fecal smear (DFS) and staining (but does not allow

identification to species level); enzyme

immunoassay (EIA);

indirect hemagglutination (IHA); Antigen detection – monoclonal

antibody; PCR for species identification.

Sometimes only the use of a fixative (formalin) is effective in detecting

cysts. Culture: From faecal samples – Robinson's medium, Jones' medium |

|

Treatment |

Metronidazole for

the invasive trophozoites PLUS a lumenal amoebicide for those still in the

intestine. Paromomycin (Humatin)

is the luminal drug of choice, since Diloxanide

furoate (Furamide)

is not commercially available in the United States or Canada (being available

only from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). A direct

comparison of efficacy showed that Paromomycin had a higher cure rat. (Humatin) should be used with caution in

patients with colitis, as it is both nephrotoxic and ototoxic. Absorption

through the damaged wall of the intestinal tract can result in permanent

hearing loss and kidney damage. Recommended dosage: metronidazole 750 mg

three times a day orally, for 5 to 10 days followed by paromomycin

30 mg/kg/day orally in 3 equal doses for 5 to 10 days or Diloxanide

furoate 500 mg 3 times a day orally for 10 days, to eradicate lumenal

amoebae and prevent relapse. |

|

Trophozoite

stage |

|

|

Pathognomonic/diagnostic

feature |

Ingested

RBC; distinctive nucleus |

|

Cyst

Stage |

|

|

Chromatoidal

body |

'Cigar'

shaped bodies (made up of crystalline ribosomes) |

|

Number

of nuclei |

1

in early stages, 4 when mature |

|

Pathognomonic/diagnostic

feature |

'Ring

and dot' nucleus and chromatoid bodies |

Meiosis

In sexually

reproducing eukaryotes, homologous recombination (HR) ordinarily occurs

during meiosis. The

meiosis-specific recombinase, Dmc1, is required for efficient

meiotic HR, and Dmc1 is expressed in E. histolytica. The purified

Dmc1 from. histolytica forms presynaptic filaments

and catalyzes ATP-dependent homologous DNA pairing and DNA strand exchange over

at least several thousand base pairs. The DNA pairing and strand

exchange reactions are enhanced by the eukaryotic meiosis-specific

recombination accessory factor (heterodimer) Hop2-Mnd1. These processes are central to meiotic

recombination, suggesting that E. histolytica undergoes

meiosis.

Several other

genes involved in both mitotic and meiotic HR are also present in E.

histolytica. HR is enhanced under stressful growth conditions (serum

starvation) concomitant with the up-regulation of HR-related genes.

Also, UV irradiation induces DNA damage in E.

histolytica trophozoites and activates the

recombinational DNA repair pathway. In particular, expression of the Rad51 protein (a recombinase) is increased

about 15-fold by UV treatment.

Jan Ricks

Jennings, MHA, LFACHE

Senior Consultant

Senior Management

Resources. LLC

412.913.0636 Cell

724.733.0509

Office

JanJenningsBlog.BlogSpot.com

March 12, 2023

This article was

published on March 12, 2023. Born on

March 12, 1945 was the notorious gangster Salvatore "Sammy the

Bull" Gravano. He is an

American former mobster who

became underboss of the Gambino crime family. Gravano played a

major role in prosecuting John Gotti, the crime

family's boss, by agreeing to testify as a government witness against him

and other mobsters in a deal in which he confessed to involvement in 19

murders.

No comments:

Post a Comment