Leprosy

Sad fac of Leprosy

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease (HD), is

a long-term infection by the bacteria Mycobacterium leprae or Mycobacterium

lepromatosis. Infection

can lead to damage of the nerves, respiratory tract, skin, and eyes. This nerve damage may result in a lack of

ability to feel pain, which can lead to the loss of parts of a person's extremities from repeated injuries or infection through unnoticed

wounds. An infected

person may also experience muscle weakness and poor eyesight. Leprosy

symptoms may begin within one year, but, for some people, symptoms may take 20

years or more to occur.

Leprosy is spread between people, although extensive

contact is necessary. Leprosy has a low pathogenicity, and 95% of people who contract M. leprae do not

develop the disease. Spread is thought to occur through a cough or contact

with fluid from the nose of a person infected by leprosy. Genetic

factors and immune function play a role in how easily a person catches the

disease. Leprosy does not spread during pregnancy to the

unborn child or through sexual contact. Leprosy occurs more commonly among people living in

poverty. There are two main types of the disease

paucibacillary and multibacillary, which differ in the number of bacteria

present. A person with paucibacillary disease has five or

fewer poorly-pigmented, numb skin patches, while a person with multibacillary

disease has more than five skin patches. The diagnosis is confirmed by finding acid-fast bacilli in a biopsy of the skin.

Leprosy is curable with multidrug therapy. Treatment

of paucibacillary leprosy is with the medications dapsone, rifampicin, and clofazimine for six months. Treatment for multibacillary leprosy uses the same

medications for 12 months. A number of other antibiotics may also be used. These

treatments are provided free of charge by the World Health

Organization.

Leprosy is not highly contagious. People

with leprosy can live with their families and go to school and work. In the

1980s, there were 5.2 million cases globally but they went down to less

than 0.2 million by 2020 ] Most

new cases occur in 14 countries, with India accounting for more than half. In

the 20 years from 1994 to 2014, 16 million people worldwide were cured of

leprosy. About 200 cases per year are reported in

the United States. Separating people

affected by leprosy by placing them in leper colonies still occurs in some areas of India, China, the

African continent, and Thailand.

· Leprosy has affected humanity for thousands of

years. The disease takes its name from the Greek word λέπρᾱ (léprā),

from λεπῐ́ς (lepís; 'scale'), while the term "Hansen's

disease" is named after the Norwegian physician Gerhard Armauer Hansen. Leprosy has historically been associated with social stigma, which continues to be a barrier to self-reporting and

early treatment. Some consider the word leper offensive,

preferring the phrase "person affected with leprosy". Leprosy

is classified as a Wneglected tropical disease. world Leprosy Day was started in 1954 to draw awareness to those

affected by leprosy.

Signs and symptoms

Common symptoms present in the different types of leprosy

include a runny nose; dry scalp; eye problems; skin lesions; muscle weakness; reddish

skin; smooth, shiny, diffuse thickening of facial skin, ear, and hand; loss of

sensation in fingers and toes; thickening of peripheral nerves; a flat nose

from destruction of nasal cartilage; and changes in phonation and other aspects of speech production. In

addition, atrophy of the testes and impotence may occur.

Leprosy can affect people in different ways. The

average incubation period is five years. People may begin to notice symptoms within the first

year or up to 20 years after infection. The first noticeable sign of

leprosy is often the development of pale or pink colored patches of skin that

may be insensitive to temperature or pain. Patches of discolored skin are sometimes accompanied

or preceded by nerve problems including numbness or tenderness in the hands or

feet. Secondary infections (additional bacterial or viral infections) can result

in tissue loss, causing fingers and toes to become shortened and deformed, as

cartilage is absorbed into the body. A person's immune response differs depending on the

form of leprosy.

Approximately 30% of people affected with leprosy

experience nerve damage. The nerve damage sustained is reversible when treated

early, but becomes permanent when appropriate treatment is delayed by several

months. Damage to nerves may cause loss of muscle function, leading to

paralysis. It may also lead to sensation abnormalities or numbness, which may lead additional infections,

ulcerations, and joint deformities.

Paucibacillary

leprosy (PB): Pale skin patch with loss of sensation

·

Skin lesions

on the thigh of a person with leprosy

·

Hands

deformed by leprosy

Cause

M. leprae and M.

lepromatosis

M. leprae,

one of the causative agents of leprosy: As an acid-fast bacterium, M. leprae appears red

when a Ziehl–Nilsen stain is used.

M. leprae and M. lepromatosis are the

mycobacteria that cause leprosy.] M. lepromatosis is

a relatively newly identified mycobacterium isolated from a fatal case of diffuse

lepromatous leprosy in

2008. M. lepromatosis is

indistinguishable clinically from M. leprae.

M. leprae is an intracellular, acid-fast bacterium that is aerobic and rod-shaped. M. leprae is

surrounded by the waxy cell envelope coating characteristic of the genus Mycobacterium.

Genetically, M. leprae and M.

lepromatosis lack the genes that are necessary for independent growth. M.

leprae and M. lepromatosis are obligate intracellular pathogens, and cannot be grown (cultured) in the laboratory.] The

inability to culture M. leprae and M. lepromatosis has

resulted in a difficulty definitively identifying the bacterial organism under

a strict interpretation of Koch's postulates.

While the causative organisms have to date been impossible

to culture in vitro, it has been possible to grow them in animals

such as mice and armadillos.

Naturally occurring infection has been reported in nonhuman

primates (including the African chimpanzee, the sooty mangabey, and the cynomolgus macaque), armadillos, and red squirrels. Multilocus sequence typing of the armadillo M. leprae strains

suggests that they were of human origin for at most a few hundred years. Thus, it is suspected that

armadillos first acquired the organism incidentally from early American

explorers.[41] This

incidental transmission was sustained in the armadillo population, and it may

be transmitted back to humans, making leprosy a zoonotic disease (spread between humans and animals).

Red squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris), a threatened species in Great Britain, were found to

carry leprosy in November 2016. It has been suggested that the

trade in red squirrel fur, highly prized in the medieval period and intensively

traded, may have been responsible for the leprosy epidemic in medieval

Europe. A pre-Norman era skull excavated in Hoxne,

Suffolk, in 2017 was found to carry DNA from

a strain of Mycobacterium leprae, which closely matched the

strain carried by modern red squirrels on Brownsea Island,

UK.

Risk factors

The greatest risk factor for developing leprosy is contact

with another person infected by leprosy. People who are

exposed to a person who has leprosy are 5–8 times more likely to develop

leprosy than members of the general population. Leprosy also occurs more

commonly among those living in poverty. Not all people who are infected with M. leprae develop

symptoms.

Conditions that reduce immune function, such as

malnutrition, other illnesses, or genetic mutations, may increase the risk of

developing leprosy. Infection with HIV does not appear to increase the

risk of developing leprosy. Certain genetic factors in the

person exposed have been associated with developing lepromatous or tuberculoid

leprosy.

Transmission

Transmission of leprosy occurs during close contact with

those who are infected. Transmission of leprosy is through the upper respiratory tract. Older research suggested the skin as the main route

of transmission, but recent research has increasingly favored the respiratory

route. Transmission occurs through inhalation of bacilli present in

upper airway secretion.

Leprosy is not sexually transmitted and is not spread

through pregnancy to the unborn child. The majority (95%) of people who

are exposed to M. leprae do not develop leprosy; casual

contact such as shaking hands and sitting next to someone with leprosy does not

lead to transmission. People are considered non-infectious 72 hours after

starting appropriate multi-drug therapy.

Two exit routes of M. leprae from the human body

often described are the skin and the nasal mucosa, although their relative

importance is not clear. Lepromatous cases show large numbers of organisms deep

in the dermis, but whether they reach the skin surface in sufficient

numbers is doubtful.

Leprosy

may also be transmitted to humans by armadillos, although the mechanism is. not fully understood.

Genetics

Not

all people who are infected or exposed to M. leprae develop leprosy,

and genetic factors are suspected to play a role in susceptibility to an

infection. Cases of leprosy often cluster in families and

several genetic variants have been identified. In many

people who are exposed, the immune system is able to eliminate the leprosy

bacteria during the early infection stage before severe symptoms develop. A

genetic defect in cell-mediated

immunity may

cause a person to be susceptible to develop leprosy symptoms after exposure to

the bacteria. The region of DNA responsible for this variability is also involved

in Parkinson's disease, giving rise to current speculation that the two disorders

may be linked at the biochemical level.

Mechanics

Most leprosy complications are the result of nerve damage.

The nerve damage occurs from direct invasion by the M. leprae bacteria

and a person's immune response resulting in inflammation. The

molecular mechanism underlying how M. leprae produces the

symptoms of leprosy is not clear,[15] but M.

leprae has been shown to bind to Schwann cells, which may lead to nerve injury including demyelination and a loss of nerve function (specifically a loss

of axonal conductance). Numerous molecular mechanisms have been associated

with this nerve damage including the presence of a laminin-binding protein and the glycoconjugate (PGL-1) on the surface

of M. leprae that can bind to laminin on peripheral nerves.

As part of the human immune response, white blood cell-derived macrophages may engulf M. leprae by phagocytosis

In the initial stages, small sensory and autonomic nerve fibers in the skin of a person with leprosy are

damaged. This damage usually results in hair loss to the area, a

loss of the ability to sweat, and numbness (decreased ability to detect

sensations such as temperature and touch). Further peripheral nerve damage may

result in skin dryness, more numbness, and muscle weaknesses or paralysis in

the area affected. The skin can crack and if the skin injuries

are not carefully cared for,

there is a risk for a secondary infection that can lead to more severe damage.

Diagnosis

Testing

for loss of sensation with monofilament

In

countries where people are frequently infected, a person is considered to have

leprosy if they have one of the following two signs:

· Skin lesion consistent with leprosy and with definite

sensory loss.

· Positive skin smears.

Skin lesions can be single or many, and usually hypopigmented, although occasionally reddish or copper-colored. The

lesions may be flat (macules), raised (papules), or solid elevated areas (nodular). Experiencing sensory loss at the skin lesion is a

feature that can help determine if the lesion is caused by leprosy or by

another disorder such as tinea versicolor. Thickened nerves are associated with leprosy

and can be accompanied by loss of sensation or muscle weakness, but muscle

weakness without the characteristic skin lesion and sensory loss is not

considered a reliable sign of leprosy.

In some cases, acid-fast leprosy bacilli in skin smears are considered diagnostic; however,

the diagnosis is typically made without laboratory tests, based on

symptoms. If a person has a new leprosy diagnosis and already

has a visible disability caused by leprosy, the diagnosis is considered late.

In countries or areas where leprosy is uncommon, such as

the United States, diagnosis of leprosy is often delayed because healthcare

providers are unaware of leprosy and its symptoms. Early

diagnosis and treatment prevent nerve involvement, the hallmark of leprosy, and

the disability it causes.

There is no recommended test to diagnose latent leprosy in

people without symptoms.T Few people with latent leprosy test positive for

anti PGL-1. The presence of M. leprae bacterial DNA can be identified using a polymerase

chain reaction (PCR)-based

technique. This molecular test alone is not sufficient to

diagnose a person, but this approach may be used to identify someone who is at

high risk of developing or transmitting leprosy such as those with few lesions

or an atypical clinical presentation.

Classification

Several

different approaches for classifying leprosy exist. There are similarities

between the classification approaches.

· The World Health Organization system distinguishes

"paucibacillary" and "multibacillary" based upon the

proliferation of bacteria. ("pauci-" refers to a low quantity.)

· The Ridley-Jopling scale provides five gradations.

· The ICD-10,

though developed by the WHO, uses Ridley-Jopling and not the WHO system. It

also adds an indeterminate ("I") entry.

· In MeSH,

three groupings are used.

Complications

Leprosy may cause the victim to lose limbs and digits but

not directly. M. leprae attacks nerve endings and destroys the body’s ability

to feel pain and injury. Without feeling pain, people injure themselves on

fire, thorns, rocks, and even hot coffee cups. Injuries become infected and

result in tissue loss. Fingers, toes, and limbs become shortened and deformed

as the tissue is absorbed into the body.

Prevention

Early detection of the disease is important, since physical

and neurological damage may be irreversible even if cured. Medications

can decrease the risk of those living with people who have leprosy from acquiring

the disease and likely those with whom people with leprosy come into contact

outside the home. The WHO recommends that preventive

medicine be given to people who are in close contact with someone who has

leprosy.[10] The

suggested preventive treatment is a single dose of rifampicin (SDR) in adults

and children over 2 years old who do not already have leprosy or

tuberculosis. Preventive treatment is associated with a 57%

reduction in infections within 2 years and a 30% reduction in infections within

6 years.

The Bacillus

Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine

offers a variable amount of protection against leprosy in addition to its

closely related target of tuberculosis. It appears to be 26% to 41% effective (based

on controlled trials) and about 60% effective based on observational studies

with two doses possibly working better than one. The WHO concluded

in 2018 that the BCG vaccine at birth reduces leprosy risk and is recommended

in countries with high incidence of TB and people who have

leprosy. People living in the same home as a person with

leprosy are suggested to take a BCG booster which may improve their immunity by

56%. Development of a more effective vaccine is ongoing

A novel vaccine called LepVax entered clinical trials in

2017 with the first encouraging results reported on 24 participants published

in 2020. If successful, this would be the first

leprosy-specific vaccine available.

Treatment

Anti-leprosy

medication

A number of leprostatic agents are available for treatment. A three-drug regimen

of rifampicin, dapsone and clofazimine is recommended for all people with leprosy, for six

months for paucibacillary leprosy and 12 months for multibacillary leprosy.

Multidrug therapy (MDT) remains highly effective, and

people are no longer infectious after the first monthly dose. It is

safe and easy to use under field conditions because of its presentation in

calendar blister packs. Post-treatment relapse rates remain

low. Resistance has been reported in several countries,

although the number of cases is small. People with

rifampicin-resistant leprosy may be treated with second line drugs such

as fluoroquinolones, minocycline, or clarithromycin, but the treatment duration is 24 months because of their

lower bactericidal activity.[90] Evidence

on the potential benefits and harms of alternative regimens for drug-resistant

leprosy is not yet available.

Skin changes

For people with nerve damage, protective footwear may help

prevent ulcers and secondary infection. Canvas shoes may be

better than PVC boots. There may be no difference between double

rocker shoes and below-knee plaster.

Topical ketanserin seems

to have a better effect on ulcer healing than clioquinol cream or zinc paste, but the evidence for this is

weak. Phenytoin applied to the skin improves skin changes to a

greater degree when compared to saline dressings.

Outcomes

Although leprosy has been curable since the mid-20th

century, left untreated it can cause permanent physical impairments and damage

to a person's nerves, skin, eyes, and limbs. Despite leprosy not

being very infectious and having a low pathogenicity, there is still

significant stigma and prejudice associated with the

disease. Because of this stigma, leprosy can affect a person's

participation in social activities and may also affect the lives of their

family and friends. People with leprosy are also at a higher

risk for problems with their mental well-being. The social stigma

may contribute to problems obtaining employment, financial difficulties, and

social isolation. Efforts to reduce discrimination and

reduce the stigma surrounding leprosy may help improve outcomes for people with

leprosy

.

Epidemiology

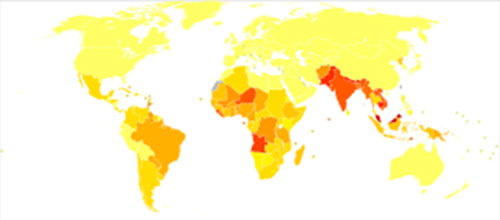

In 2018, there were 208,619 new cases of leprosy recorded,

a slight decrease from 2017. In 2015, 94% of the new leprosy cases were

confined to 14 countries. India reported the greatest number of new cases (60%

of reported cases), followed by Brazil (13%) and Indonesia (8%). Although the number of cases worldwide continues to

fall, there are parts of the world where leprosy is more common, including

Brazil, South Asia (India, Nepal, Bhutan), some parts of Africa (Tanzania,

Madagascar, Mozambique), and the western Pacific.[98] About

150 to 250 cases are diagnosed in the United States each year.

In the 1960s, there were tens of millions of leprosy cases recorded

when the bacteria started to develop resistance to dapsone, the most common treatment option at the time. International

(e.g., the WHO's "Global Strategy for Reducing Disease Burden Due to

Leprosy") and national (e.g., the International Federation of Anti-Leprosy

Associations) initiatives have reduced the total number and the number of new

cases of the disease.

Disease burden

The number of new leprosy cases is difficult to measure and

monitor because of leprosy's long incubation period, delays in diagnosis after

onset of the disease, and lack of medical care in affected areas. The

registered prevalence of the disease is used to determine disease burden. Registered prevalence is a useful proxy indicator of

the disease burden, as it reflects the number of active leprosy cases diagnosed

with the disease and receiving treatment with MDT at a given point in

time. The prevalence rate is defined as the number of cases registered for

MDT treatment among the population in which the cases have occurred, again at a

given point in time.

History

G. H. A.

Hansen, discoverer of M. leprae

Historical distribution

Using comparative genomics, in 2005, geneticists traced the origins and worldwide

distribution of leprosy from East Africa or the Near East along human migration

routes. They found four strains of M. leprae with specific

regional locations: ] Monot et

al. (2005) determined that leprosy originated in East Africa

or the Near East and traveled with humans along their migration routes,

including those of trade in goods and slaves. The four strains of M. leprae are

based in specific geographic regions where each predominantly occurs:

· strain 1 in Asia, the Pacific region, and East Africa;

· strain 2 in Ethiopia, Malawi, Nepal, north India, and New Caledonia;

· strain 3 in Europe, North Africa, and the Americas;

· strain 4 in West Africa and the Caribbean.

This confirms the spread of the disease along the

migration, colonization, and slave trade routes taken from East Africa to

India, West Africa to the New World, and from Africa into Europe and vice

versa.

Skeletal remains discovered in 2009 represent the oldest

documented evidence for leprosy, dating to the 2nd millennium BC. Located at Balathal, Rajasthan, in northwest India, the discoverers suggest

that, if the disease did migrate from Africa to India during the 3rd millennium BC "at a time when there was substantial

interaction among the Indus Civilization, Mesopotamia, and Egypt, there needs

to be additional skeletal and molecular evidence of leprosy in India and Africa

to confirm theAffrican origin of the disease." A proven human case

was verified by DNA taken from the shrouded remains of a man discovered by

researchers from the Hebrew

University of Jerusalem in

a tomb next to the Old City of Jerusalem, Israel, dated by radiocarbon methods to the first half of the 1st

century.

Pick up here down from here.

The oldest strains of leprosy known from Europe are

from Great Chesterford in southeast England and dating back to AD 415–545.

These findings suggest a different path for the spread of leprosy, meaning it

may have originated in Western Eurasia. This study also indicates that there

were more strains in Europe at the time than previously determined.

Discovery and scientific progress

Literary attestation of leprosy is unclear because of the

ambiguity of many early sources, including the Indian Atharvaveda and Kausika Sutra, the Egyptian Ebers papyrus,

and the Hebrew Bible's various sections regarding signs of impurity (tzaraath). Clearly leprotic symptoms are

attested in the Indian doctor Sushruta's Compendium, originally dating to c. 600 BC but only

surviving in emended texts no earlier than the 5th century. They were

separately described by Hippocrates in 460 BC. However, Hansen's disease probably

did not exist in Greece or the Middle East before the Common Era. In 1846, Francis Adams produced The Seven Books of Paulus Aegineta which

included a commentary on all medical and surgical knowledge and descriptions

and remedies to do with leprosy from the Romans, Greeks, and Arabs.

Leprosy did not exist in the Americas before colonization by modern Europeans] nor

did it exist in Polynesia until the middle of the 19th century.

Distribution of leprosy around the world in 1891

The

causative agent of leprosy, M. leprae, was discovered by G. H. Armauer

Hansen in Norway in 1873, making it the

first bacterium to be identified as causing disease in humans.

Treatment

The

first effective treatment (promin) became available in the 1940s. In the

1950s, dapsone was introduced. The search for further effective

antileprosy drugs led to the use of clofazimine and rifampicin in the 1960s and 1970s.[121] Later,

Indian scientist Shantaram Yawalkar and his colleagues formulated a combined

therapy using rifampicin and dapsone, intended to mitigate bacterial

resistance. Multi-drug

therapy (MDT) combining all three drugs was first recommended by the WHO in 1981. These three antileprosy drugs are still used

in the standard MDT regimens.

Leprosy

was once believed to be highly contagious and was treated with mercury, as was syphilis, which was first described in 1530. Many early cases

thought to be leprosy could actually have been syphilis.

Resistance

has developed to initial treatment. Until the introduction of MDT in the early

1980s, leprosy could not be diagnosed and treated successfully within the

community.

Japan still has sanatoriums (although Japan's sanatoriums

no longer have active leprosy cases, nor are survivors held in them by law).

The

importance of the nasal mucosa in the transmission of M leprae was recognized as early as 1898 by Schäffer, in

particular, that of the ulcerated mucosa. The mechanism of plantar

ulceration in leprosy and its treatment was first described by Dr Ernest W Price.

Etymology

The

word "leprosy" comes from the Greek word "λέπος (lépos) –

skin" and "λεπερός (leperós) – scaly man".

Society and culture

Two lepers denied entrance to town, 14th

India

British India enacted the Leprosy Act of 1898 which

institutionalized those affected and segregated them by sex to prevent

reproduction. The act was difficult to enforce but was repealed in 1983 only

after multidrug therapy had become widely available. In 1983, the National

Leprosy Elimination Programme, previously the National Leprosy Control

Programme, changed its methods from surveillance to the treatment of people

with leprosy. India still accounts for over half of the global disease burden.

According to WHO, new cases in India during 2019 diminished to 114,451 patients

(57% of the world's total new cases). Until 2019, one could justify a

petition for divorce with the spouse's diagnosis of leprosy.

Treatment cost

Between 1995 and 1999, the WHO, with the aid of the Nippon Foundation, supplied all endemic countries with free multidrug

therapy in blister packs, channeled through ministries of health.

This free provision was extended in 2000 and again in 2005, 2010

and 2015 with donations by the multidrug therapy manufacturer Novartis through the WHO. In the latest agreement signed

between the company and the WHO in October 2015, the provision of free

multidrug therapy by the WHO to all endemic countries will run until the end of

2025. At the national level, nongovernment

organizations affiliated with the national

program will continue to be provided with an appropriate free supply of

multidrug therapy by the WHO.

Historical texts

Written accounts of leprosy date back thousands of years.

Various skin diseases translated as leprosy appear in the ancient Indian text,

the Atharava Veda,

by 600 BC. Another Indian text, the Manusmriti (200

BC), prohibited contact with those infected with the disease and made

marriage to a person infected with leprosy punishable.

The Hebraic root tsara or tsaraath (צָרַע, – tsaw-rah' – to be

struck with leprosy, to be leprous) and the Greek (λεπρός–lepros), are of

broader classification than the more narrow use of the term related to Hansen's

Disease. Any progressive skin disease (a whitening or

splotchy bleaching of the skin, raised manifestations of scales, scabs,

infections, rashes, etc....), as well as generalized molds and surface

discoloration of any clothing, leather, or discoloration on walls or surfaces

throughout homes all, came under the "law of leprosy" (Leviticus

14:54–57).[138] Ancient

sources such as the Talmud (Sifra

make clear that tzaraath refers to various

types of lesions or stains associated with ritual impurity and occurring on cloth, leather, or houses, as well

as skin. Traditional Judaism and Jewish rabbinical authorities, both historical

and modern, emphasize that the tsaraath of Leviticus is a

spiritual ailment with no direct relationship to Hansen's disease or phyical

contagions. The relation of tsaraath to "leprosy"

comes from translations of Hebrew Biblical texts into Greek and ensuing

misconceptions

All three Synoptic Gospels of the New Testament describe instances of Jesus healing people with

leprosy (Matthew 8:1–4, Mark 1:40–45,

and Luke 5:12–16).

The Bible's description of leprosy is congruous (if lacking detail) with the

symptoms of modern leprosy, but the relationship between this disease, tzaraath,

and Hansen's disease has been disputed.[140] The

biblical perception that people with leprosy were unclean can be found in a

passage from Leviticus 13: 44–46. While this text defines the leper as impure, it did not explicitly make a moral judgement on those

with leprosy.[141] Some Early Christians believed that those affected by leprosy were being

punished by God for sinful behavior. Moral associations have persisted

throughout history. Pope Gregory the Great (540–604) and Isidor of Seville (560–636) considered people with the disease to be

heretics.

Middle

Ages

Medieval leper

The social perception of leprosy in the general population

was in general mixed. On one hand, people feared getting infected with the

disease and thought of people suspected of leprosy to be unclean,

untrustworthy, and occasionally morally corrupt. On the other hand, Jesus'

interaction with lepers, the writing of church leaders and the Christian focus

on charitable works led to viewing the lepers as "chosen by God or

seeing the disease as a means of obtaining access to heaven.

Early medieval understanding of leprosy was influenced by

early Christian writers such as Gregory of Nazianzus and John Chrysostom, whose writings were later embraced by Byzantine and Latin

writers. Gregory, for example, did not only compose sermons

urging Christians to assist victims of the disease, but also condemned pagans

or Christians who justified rejecting lepers on the allegation that God had

sent them the disease to punish them. As cases of leprosy increased during

these years in the Eastern Roman Empire, becoming a major health issue, the ecclesiastic leaders

of the time discussed how to assist those affected as well as change the

attitude of society towards them. They also tried this by using the name

"Holy disease" instead of the commonly used "Elephant's

disease" (elephantiasis), implying that God did not create this disease to

punish people but to purify them for heaven.[146] Although

not always successful in persuading the public and a cure was never found by

Greek medicians, they created an environment where victims could get palliative care and were never expressly banned from society, as

sometimes happened in Western Europe. Theodore Balsamon, a 12th century jurist

in Constantinople, noted that lepers were allowed to enter the same

churches, cities and assemblies that healthy people attended.

As the disease became more prevalent in Western Europe in

the fifth century, first efforts to set up permanent institutions to house and

feed lepers. These efforts were, inclusively, the work of bishops in France at

the end of the sixth century, such as in Chalon-sur-Saône. The

increase in hospitals or leprosaria (sing. leprosarium) that treated people with leprosy

in the 12th and 13th century seems to indicate a rise in cases, possibly

in connection with the increase in urbanification as well as returning

crusaders from the Middle East.[145] France

alone had nearly 2,000 leprosaria during this period. Additionally

to the new leprosia, further steps were taken by secular and religious leaders

to prevent further spread of the disease. The third Lateran Council of 1179 required lepers to have their own priests and

churches and a 1346 edict by King Edward expelled lepers from city limits. Segregation from

mainstream society became common, and people with leprosy were often required

to wear clothing that identified them as such or carry a bell announcing their

presence. As

in the East, it was the Church who took care of the lepers due to the still

persisting moral stigma and who ran the leprosaria. Although

the leprosaria in Western Europe removed the sick from society, they were never

a place to quarantine them or from which they could not leave: lepers would go

beg for alms for the upkeep of the leprosaria or meet with their families.

19th

century

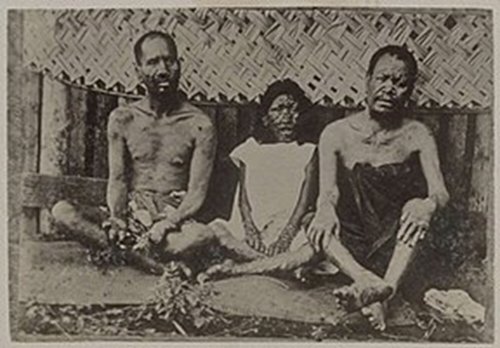

24-year-old

A man with leprosy (1886)

Norway

Norway

was the location of a progressive stance on leprosy tracking and treatment and

played an influential role in European understanding of the disease. In 1832,

Dr. JJ Hjort conducted the first leprosy survey, thus establishing a basis for

epidemiological surveys. Subsequent surveys resulted in the establishment of a

national leprosy registry to study the causes of leprosy and for tracking the

rate of infection.

Early

leprosy research throughout Europe was conducted by Norwegian scientists Daniel

Cornelius Danielssen and Carl Wilhelm Boeck. Their work resulted in the establishment of the National

Leprosy Research and Treatment Center. Danielssen and Boeck believed the cause

of leprosy transmission was hereditary. This stance was influential in

advocating for the isolation of those infected by sex to prevent reproduction.

Colonialism

and imperialism

Father Damien on his deathbed in 1889

Though leprosy in Europe was again on the decline by the 1860s,

Western countries embraced isolation treatment out of fear of the spread of

disease from developing countries, minimal understanding of bacteriology, lack of diagnostic

ability or knowledge of how contagious the disease was, and missionary

activity. Growing imperialism and pressures of the industrial

revolution resulted in a Western presence in countries where leprosy

was endemic, namely the British presence in India. Isolation treatment methods were observed by

Surgeon-Mayor Henry Vandyke Carter of the British Colony in India while visiting Norway,

and these methods were applied in India with the financial and logistical

assistance of religious missionaries. Colonial and religious influence and associated stigma

continued to be a major factor in the treatment and public perception of

leprosy in endemic developing countries until the mid-twentieth century.

20th

century United States

The

National Leprosarium at Carville, Louisiana, known in 1955 as the Louisiana Leper Home, was the only

leprosy hospital on the mainland United States. Leprosy patients from all over

the United States were sent to Carville in order to be kept in isolation away

from the public, as not much about leprosy transmission was known at the time

and stigma against those with leprosy was high (see Leprosy stigma). The Carville leprosarium was known for its innovations

in reconstructive surgery for those with leprosy. In 1941, 22 patients at

Carville underwent trials for a new drug called promin. The results were described as miraculous, and soon after

the success of promin came dapsone, a medicine even more effective in the fight against

leprosy.

Stigma

Despite

now effective treatment and education efforts, leprosy stigma continues to be

problematic in developing countries where the disease is common. Leprosy is

most common amongst impoverished populations where social stigma is likely to

be compounded by poverty. Fears of ostracism, loss of employment, or expulsion

from family and society may contribute to a delayed diagnosis and treatment.

Folk beliefs, lack of education, and religious connotations

of the disease continue to influence social perceptions of those affected in

many parts of the world. In Brazil, for example, folklore holds that leprosy is

a disease transmitted by dogs, or that it is associated with sexual

promiscuity, or that it is a punishment for sins or moral transgressions

(distinct from other diseases and misfortunes, which are in general thought of

as being according to the will of God).[158] Socioeconomic

factors also have a direct impact. Lower-class domestic workers who are often

employed by those in a higher socioeconomic class may find their employment in

jeopardy as physical manifestations of the disease become apparent. Skin

discoloration and darker pigmentation resulting from the disease also have

social repercussions.

In extreme cases in northern India, leprosy is equated with

an "untouchable" status that "often persists long after

individuals with leprosy have been cured of the disease, creating lifelong

prospects of divorce, eviction, loss of employment, and ostracism from family

and social networks."

·

Leprosy

·

A 26-year-old woman with leprous

lesions

·

A 13-year-old boy with severe leprosy

Public Policy

A goal of the World Health Organization is to

"eliminate leprosy" and in 2016 the organization launched

"Global Leprosy Strategy 2016–2020 Elimination of leprosy is defined

as "reducing the proportion of leprosy patients in the community to very

low levels, specifically to below one case per 10,000 population".] Diagnosis

and treatment with multidrug thepre effective, and a 45% decline in disease

burden has ocurred since multidrug therapy has become more widely

available. The organization emphasizes the importance of fully integrating

leprosy treatment into public health services, effective diagnosis and

treatment, and access to information. The approach includes supporting an

increase in health care professionals who understand the disease, and a

coordinated and renewed political commitment that includes coordination between

countries and improvements in the methodology for collecting and analysing

data.

Interventions

in the "Global Leprosy Strategy 2016–2020: Accelerating towards a

leprosy-free world":

· Early detection of cases focusing on children to reduce transmission

and disabilities.

· Enhanced healthcare services and improved access for people

who may be marginalized.

· For countries where leprosy is endemic, further

interventions include an improved screening of close contacts, improved treatment

regimens, and interventions to reduce stigma and discrimination against people

who have leprosy.

·

Community-based

interventions

In

some instances in India, community-based rehabilitation is embraced by local

governments and NGOs alike. Often, the identity cultivated by a community

environment is preferable to reintegration, and models of self-management and

collective agency independent of NGOs and government support have been

desirable and successful.

Notable cases

· Josephine Cafrine of Seychelles had leprosy from the age of 12 and kept a personal

journal that documented her struggles and suffering.[165][166][167] It

was published as an autobiography in 1923.

· Saint Damien De Veuster, a Roman Catholic priest from Belgium, himself eventually

contracting leprosy, ministered to lepers who had been placed under a

government-sanctioned medical quarantine on the island of Molokaʻi in the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi.

· Baldwin IV of

Jerusalem was a

Christian king of Latin Jerusalem who had leprosy.

· Josefina Guerrero was a Filipino spy during World War II, who used the Japanese fear of her leprosy to listen to

their battle plans and deliver the information to the American forces

under Douglas MacArthur.

· King Henry IV of England (reigned 1399 to 1413) possibly had leprosy.

· Vietn

· Ōtani Yoshitsugu, a Japanese daimyō

Leprosy in the media

· English author Graham Greene's novel A Burnt-Out Case is set in a leper colony in Belgian Congo. The story

is also predominantly about a disillusioned architect working with a doctor on

devising new cure and amenities for mutilated victims of lepers; the title,

too, refers to the condition of mutilation and disfigurement in the disease.

· Death metal band Death (metal band) has an album titled “Leprosy”.

· Forugh Farrokhzad made a 22-minute documentary about a leprosy colony

in Iran in 1962 titled The House Is

Black. The film

humanizes the people affected and opens by saying that "there is no

shortage of ugliness in the world, but by closing our eyes on ugliness, we will

intensify it."

· Moloka'i is a novel by Alan Brennert about a leper colony in Hawaii. This novel follows

the story of a seven-year-old girl taken from her family and put on the small

Hawaiian island of Molokai's leper settlement. Even though this is a fiction novel it

is based upon some very true and revealing incidents which occurred at this

Leprosy settlement.

· Jack London in 1909 published Koolau the Leper in his Tales of Hawai'i about

Molokai and people consigned to it circa 1893.

· The lead character in The

Chronicles of Thomas Covenant by Stephen R. Donaldson suffers from leprosy. His condition seems to be cured

by the magic of the fantasy land he finds himself in, but he resists believing

in its reality, for example, by continuing to perform a regular visual

surveillance of extremities as

a safety check. Donaldson gained experience with the disease as a young man in

India, where his father worked in a missionary for people with leprosy.

· In House of the

Dragon, the TV

adaptation of George R. R. Martin's Fire

and Blood, King Viserys

I Targaryen suffers from a debilitating disease where parts of

his body develop lesions and slowly rot away over time. Paddy Considine, the actor playing the role, explained on a podcast with Entertainment Weekly that Viserys suffers from "a form of

leprosy". Leprosy is not mentioned in the novel, where Viserys

instead suffers from various health issues relating to his obesity, including

infections and gout.

Infection of animals

Wild nine-banded

armadillos (Dasypus

novemcinctus) in south central United States often carry Mycobacterium leprae. This

is believed to be because armadillos have a low body temperature. Leprosy

lesions appear mainly in cooler body regions such as the skin and mucous

membranes of the upper

respiratory tract.

Because of armadillos' armor, skin lesions are hard to

see. Abrasions around the eyes, nose and feet are the most common

signs. Infected armadillos make up a large reservoir of M. leprae and

may be a source of infection for some humans in the United States or other

locations in the armadillos' home range. In armadillo leprosy, lesions do not

persist at the site of entry in animals, M. leprae multiply in macrophages at the site of inoculation and lymph nodes.

A recent outbreak in chimpanzees in West Africa is showing

that the bacteria can infect another species and also possibly have additional

rodent hosts.

Recent studies have demonstrated that the disease is

endemic in the UK red Eurasian squirrel population, with Mycobacterium

leprae and Mycobacterium lepromatosis appearing in different

populations. The Mycobacteria leprae strain discovered on Brownsea

Island is equated to one thought to have died out in the human

population in mediaeval times. Despite this, and speculation

regarding past transmission through trade in squirrel furs, there does not seem

to be a high risk of squirrel to human transmission from the wild population.

Although Leprosy continues to be diagnosed in immigrants to the UK, the last

known human case of leprosy arising in the UK was recorded over 200 years ago.

It has been shown that leprosy can reprogram cells in

mouse and armadillos models similarly as how Induced

pluripotent stem cells are

generated by the transcription

factors Myc, Oct3/4, Sox2 and Klf4.

Jan

Ricks Jennings, MHA , LFACHE

Senior

Consultant

Senior Management Resources, LLC

JanJenningsBlog.Blogspot.com

412.913.0636

Cell

724.733.0509

Office