Coccidioidomycosis or Valley

Coccidioidomycosis commonly known

as cocci

Valley fever, well as California

fever, desert rheumatism, or San Joaquin Valley fever,[4] is

a mammalian fungal disease caused

by Coccidioides immitis or Coccidioides posadasii.[5] Coccidioidomycosis

is endemic in certain parts

of the United States in Arizona, California, Nevada, New

Mexico, Texas, Utah,

and northern Mexico.[6]

C. immitis is

a dimorphic saprophytic fungus

that grows as a mycelium in

the soil and produces a spherule form

in the host organism.

It resides in the soil in

certain parts of the southwestern United States, most notably in California and Arizona. It

is also commonly found in northern Mexico, and parts of Central and South America. C.

immitis is dormant during long dry spells, then develops as a mold with

long filaments that break off into airborne spores when

it rains. The spores, known as arthroconidia,

are swept into the air by disruption of the soil, such as during construction,

farming, low-wind or singular dust events, or an earthquake. Windstorms

may also cause epidemics far from endemic areas. In December 1977, a windstorm

in an endemic area around Arvin,

California led to several hundred cases,

including deaths, in non-endemic areas hundreds of miles away.

Coccidioidomycosis is a common cause

of community-acquired pneumonia in

the endemic areas of the United States. Infections

usually occur due to inhalation of the arthroconidial spores after soil

disruption. The

disease is not contagious. In

some cases the infection may recur or become chronical

It was reported in 2022 that valley fever

had been increasing in California's Central Valley for years (1,000 cases

in Kern county in

2014, 3,000 in 2021); experts said that cases could rise across the American

west as the climate makes the landscape drier and hotter.

Classification

After Coccidioides infection,

coccidioidomycosis begins with Valley fever, which is its initial acute form.

Valley fever may progress to the chronic form and then to disseminated coccidioidomycosis.

Therefore, coccidioidomycosis may be divided into the following types:

·

Acute coccidioidomycosis, sometimes

described in literature as primary pulmonary coccidioidomycosis

·

Chronic coccidioidomycosis

·

Disseminated coccidioidomycosis,

which includes primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis

Valley fever is not a contagious disease.

Signs and symptoms

A skin lesion

due to Coccidioides infection

An estimated 60% of people infected with

the fungi responsible for coccidioidomycosis have minimal to no symptoms, while

40% will have a range of possible clinical symptoms. Of

those who do develop symptoms, the primary infection is most often respiratory,

with symptoms resembling bronchitis or pneumonia that

resolve over a matter of a few weeks. In endemic regions, coccidioidomycosis is

responsible for 20% of cases of community-acquired pneumonia Notable coccidioidomycosis signs and symptoms

include a profound feeling of tiredness,

loss of smell and taste, fever,

cough, headaches, rash, muscle pain,

and joint pain.[3] Fatigue

capersist for many months after initial infection. The

classic triad of coccidioidomycosis known as "desert rheumatism"

includes the combination of fever, joint pains, and erythema nodosum.

A minority (3–5%) of infected individuals

do not recover from the initial acute infection and develop a chronic

infection. This can take the form of chronic lung infection or widespread

disseminated infection (affecting the tissues

lining the brain, soft

tissues, joints, and bone). Chronic infection is responsible for most of the

morbidity and mortality. Chronic fibrocavitary disease is manifested by cough

(sometimes productive of mucus), fevers, night sweats and weight loss Osteomyelitis,

including involvement of the spine, and meningitis may

occur months to years after initial infection. Severe lung disease may develop

in HIV-infected

persons.

Complications

Serious complications may occur in patients who have weakened immune systems, including severe pneumonia with respiratory failure and bronchopleural fistulas requiring resection, lung nodules, and possible disseminated form, where the infection spreads throughout the body. The disseminated form of coccidioidomycosis can devastate the body, causing skin ulcers, abscesses, bone lesions, swollen joints with severe pain, heart inflammation, urinary tract problems, and inflammation of the brain's lining, which can lead to death.

Cause

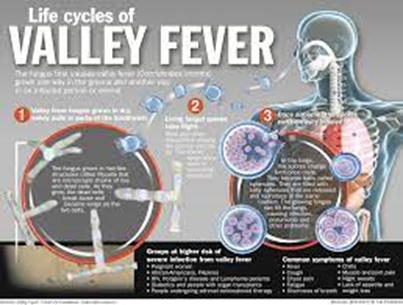

Life cycle

of Coccidioides

Both Coccidioides species

share the same asexual

life cycle, switching between saprobic (on

left) and parasitic (on

right) life stages.

Rain starts the cycle of initial growth

of the fungus in the soil. In

soil (and in agar media), Coccidioides exist

in filament form. It forms hyphae in

both horizontal and vertical directions. Over a prolonged dry period, cells

within hyphae degenerate to form alternating barrel-shaped cells (arthroconidia)

which are light in weight and carried by air currents. This happens when the

soil is disturbed, often by clearing trees, construction or farming. As the

population grows, so do all these activities, causing a potential cascade

effect. The more land that is cleared and the more arid the soil, the riper the

environment for Coccidioides. These spores can be easily

inhaled unknowingly. On reaching alveoli they

enlarge in size to become spherules, and internal septations develop.

This division of cells is made possible by the optimal temperature inside the

body. Septations

develop and form endospores within

the spherule. Rupture of spherules release these endospores, which in turn

repeat the cycle and spread the infection to adjacent tissues within the body

of the infected individual. Nodules can

form in lungs surrounding these spherules. When they rupture, they release

their contents into bronchi, forming thin-walled cavities. These cavities can

cause symptoms including characteristic chest pain, coughing up blood,

and persistent cough. In individuals with a weakened immune system, the

infection can spread through

the blood. The fungus can also, rarely,

enter the body through a break in the skin and cause infection.

Diagnosis

Coccidioidomycosis diagnosis relies on a

combination of an infected person's signs and symptoms, findings on

radiographic imaging, and laboratory results.[3] The

disease is commonly misdiagnosed as bacterial community-acquired

pneumonia.[3] The

fungal infection can be demonstrated by microscopic detection of diagnostic

cells in body fluids, exudates, sputum and biopsy tissue

by methods of Papanicolaou or Grocott's methenamine silver staining. These stains

can demonstrate spherules and surrounding inflammation.

With specific nucleotide primers, C.

immitis DNA can

be amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

It can also be detected in culture by morphological identification or by using

molecular probes that hybridize with C. immitis RNA. C.

immitis and C. posadasii cannot be distinguished on

cytology or by symptoms, but only by DNA PCR.

An indirect demonstration of fungal

infection can be achieved also by serologic analysis detecting fungal antigen or

host IgM or IgG antibody produced

against the fungus. The available tests include the tube-precipitin (TP)

assays, complement fixation assays,

and enzyme immunoassays.

TP antibody is not found in cerebrospinal

fluid (CSF). TP antibody is specific and

is used as a confirmatory test, whereas ELISA is sensitive and

thus used for initial

testing.[

If the meninges are affected, CSF will

show abnormally low glucose levels,

an increased level of protein, and lymphocytic pleocytosis.

Rarely, CSF eosinophilia is presen1

Chest X-rays rarely

demonstrate nodules or cavities in the lungs, but these images commonly

demonstrate lung opacification, associated with the lungs. Computed

tomography scans of the chest are more

sensitive than chest X-rays to detect these changes.

Prevention

Preventing Valley fever is challenging

because it is difficult to avoid breathing in the fungus should it be present;

however, the public health effect of the disease is essential to understand in

areas where the fungus is endemic. Enhancing surveillance of coccidioidomycosis

is key to preparedness in the medical field in addition to improving

diagnostics for early infections. Currently there are no completely effective

preventive measures available for people who live or travel through Valley

fever-endemic areas. Recommended preventive measures include avoiding airborne

dust or dirt, but this does not guarantee protection against infection. People

in certain occupations may be advised to wear face masks. The use

of air filtration indoors is also helpful, in addition to keeping skin injuries

clean and covered to avoid skin infection.

In 1998–2011, there were 111,117 cases of

coccidioidomycosis in the U.S. that were logged into the National

Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS). Since many U.S. states do not require

reporting of coccidioidomycosis, the actual numbers may be higher. The United

States' Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) called

the disease a "silent epidemic" and acknowledged that there is no

proven anticoccidioidal vaccine available. A

2001 cost-effectiveness analysis indicated

that a potential vaccine could improve health as well as reducing total health

care expenditures among infants, teens, and immigrant adults, and more modestly

improve health but increase total health care expenditures in older age groups.

Raising both surveillance and awareness

of the disease while medical researchers are developing a human vaccine can

positively contribute towards prevention efforts. Research

demonstrates that patients from endemic areas who are aware of the disease are

most likely to request diagnostic testing for

coccidioidomycosis. Presently, Meridian Bioscience manufactures the

so-called EIA test to diagnose the Valley fever, which however

is known for producing a fair quantity of false positives. Currently,

recommended prevention measures can include type-of-exposure-based respirator

protection for persons engaged in agriculture, construction and others working

outdoors in endemic areas. Dust control measures such as planting grass

and wetting the soil, and also limiting exposure to dust storms are advisable

for residential areas in endemic regions.

Treatment

Significant disease develops in fewer

than 5% of those infected and typically occurs in those with a weakened immune

system. Mild asymptomatic cases often do not require

any treatment. Those with severe symptoms may benefit from antifungal therapy,

which requires 3–6 months or more of treatment depending on the response to the

treatment. There is a lack of prospective studies that

examine optimal antifungal therapy for coccidioidomycosis.

On the whole, oral fluconazole and intravenous amphotericin B are

used in progressive or disseminated disease, or in immunocompromised

individuals. Amphotericin

B was originally the only available treatment, but

alternatives, including itraconazole and ketoconazole,

became available for milder disease. Fluconazole is the preferred medication for

coccidioidal meningitis, due to its penetration into CSF. Intrathecal or intraventricular amphotericin

B therapy is used if infection persists after fluconazole treatment. Itraconazole

is used for cases that involve treatment of infected person's bones and joints.

The antifungal medications posaconazole and voriconazole have

also been used to treat coccidioidomycosis. Because the symptoms of

coccidioidomycosis are similar to the common flu, pneumonia,

and other respiratory diseases, it is important for public health professionals

to be aware of the rise of coccidioidomycosis and the specifics of

diagnosis. Greyhound dogs

often get coccidioidomycosis; their treatment regimen involves 6–12 months of

ketoconazole taken with food.

A particular severe case of meningitis

caused by valley fever initially received several incorrect diagnoses such as

sinus infections and cluster headaches. The patient became unable to work

during diagnosis and original search for treatments. Eventually the right

treatment was found—albeit with severe side effects—requiring four pills a day

and medication administered directly into the brain every 16 weeks.

Toxicity

Conventional amphotericin B

desoxycholate (AmB:

used since the 1950s as a primary agent) is known to be associated with

increased drug-induced nephrotoxicity impairing kidney function.

Other

formulations have been developed such as lipid-soluble formulations to mitigate

side-effects such as direct proximal and distal tubular cytotoxicity.

These include liposomal amphotericin B, amphotericin

B lipid complex such as Abelcet (brand) amphotericin B

phospholipid complex[35] also

as AmBisome Intravenous, or Amphotec

Intravenous (Generic; Amphotericin B Cholesteryl Sul), and amphotericin

B colloidal dispersion, all shown to exhibit a decrease in nephrotoxicity.

The latter was not as effective in one study as amphotericin B

desoxycholate which had a 50% murine (rat

and mouse) morbidity rate versus zero for the AmB colloidal dispersion.

The cost of the nephrotoxic AmB

deoxycholate, in 2015, for a patient of 70 kilograms (150 lb) at

1 mg/kg/day dosage, was approximately US$63.80,

compared to $1318.80 for 5 mg/kg/day of the less toxic liposomal AmB.

Epidemiology

Coccidioidomycosis is endemic to the

western hemisphere between 40°N and 40°S. The ecological niches are

characterized by hot summers and mild winters with an annual rainfall of

10–50 cm. The species are found in alkaline sandy soil,

typically 10–30 cm below the surface. In harmony with the mycelium life

cycle, incidence increases with periods of dryness after a rainy season; this

phenomenon, termed "grow and blow", refers to growth of the fungus in

wet weather, producing spores which are spread by the wind dur

North America

In the United States, immitis is

endemic to southern and central California with the highest presence in

the San

Joaquin Valley. C.

posadassi is most prevalent in Arizona, although it can be found in a

wider region spanning from Utah, New Mexico, Texas, and Nevada. An estimated

150,000 infections occur annually, with 25,000 new infections occurring every

year.[contradictory] The

incidence of coccidioidomycosis in the United States in 2011 (42.6 per 100,000)

was almost ten times higher than the incidence reported in 1998 (5.3 per

100,000). In area where it is most prevalent, the infection rate is 2-4%.

Incidence varies widely across the west

and southwest. In Arizona, for instance, in 2007, there were 3,450 cases

in Maricopa County, which in

2007 had an estimated population of 3,880,181 for

an incidence of approximately 1 in 1,125. In

contrast, though southern New Mexico is considered an endemic region, there

were 35 cases in the entire state in 2008 and 23 in 2007, in

a region that had an estimated 2008 population of 1,984,356, for

an incidence of approximately 1 in 56,695.

Infection rates vary greatly by county,

and although population density is important, so are other factors that have

not been proven yet. Greater construction activity may disturb spores in the

soil. In addition, the effect of altitude on fungi growth and morphology has

not been studied, and altitude can range from sea level to 10,000 feet or

higher across California, Arizona, Utah and New Mexico.[

In California from 2000 to 2007, there

were 16,970 reported cases (5.9 per 100,000 people) and 752 deaths of the 8,657

people hospitalized. The highest incidence was in the San Joaquin Valley with

76% of the 16,970 cases (12,855) occurring in the area.[45] Following

the 1994 Northridge earthquake,

there was a sudden increase of cases in the areas affected by the quake, at a

pace of over 10 times baseline.

There was an outbreak in the summer of

2001 in Colorado, away from where the disease was considered endemic. A group

of archeologists visited Dinosaur National Monument,

and eight members of the crew, along with two National Park Service workers

were diagnosed with Valley fever.

California state prisons, beginning in

1919, have been particularly affected by coccidioidomycosis. In 2005 and 2006,

the Pleasant

Valley State Prison near Coalinga and Avenal State Prison near Avenal on

the western side of the San Joaquin Valley had

the highest incidence in 2005, of at least 3,000 per 100,000. The receiver appointed

in Plata v. Schwarzenegger issued

an order in May 2013 requiring relocation of vulnerable populations in those

prisons. The incidence rate has been increasing, with rates as high as 7%

during 2006–2010. The cost of care and treatment is $23 million in California

prisons. A lawsuit was filed against the state in 2014 on behalf of 58 inmates

stating that the Avenal and Pleasant valley state prisons did not take

necessary steps to prevent infections.

Population

risk factore

There are several populations that have a

higher risk for contracting coccidioidomycosis and developing the advanced

disseminated version of the disease. Populations with exposure to the airborne

arthroconidia working in agriculture and construction have a higher risk.

Outbreaks have also been linked to earthquakes, windstorms and military

training exercises where the ground is disturbed.[40] Historically,

an infection is more likely to occur in males than females, although this could

be attributed to occupation rather than being sex-specific. Women

who are pregnant and immediately postpartum are at a high risk of infection and

dissemination. There is also an association between stage of pregnancy and

severity of the disease, with third trimester women being more likely to

develop dissemination. Presumably this is related to highly elevated hormonal

levels, which stimulate growth and maturation of spherules and subsequent

release of endospores. Certain

ethnic populations are more susceptible to disseminated coccidioidomycosis. The

risk of dissemination is 175 times greater in Filipinos and 10 times greater in

African Americans than non-Hispanic whites. Individuals

with a weakened immune system are also more susceptible to the disease. In

particular, individuals with HIV and

diseases that impair T-cell function.

Individuals with pre-existing conditions such as diabetes are also at a higher

risk. Age also affects the severity of the disease, with more than one-third of

deaths being in the 65-84 age group.

The first case of what was later named

coccidioidomycosis was described in 1892 in Buenos Aires by Alejandro Posadas,

a medical intern at the Hospital

de Clínicas "José

de San Martín". Posadas

established an infectious character of the disease after being able to transfer

it in laboratory conditions to lab animals. In

the U.S., Dr. E. Rixford, a physician from a San Francisco hospital, and T. C.

Gilchrist, a pathologist at Johns Hopkins Medical School, became early pioneers

of clinical studies of the infection. They

decided that the causative organism was a Coccidia-type protozoan and

named it Coccidioides immitis (resembling Coccidia,

not mild).

Dr. William Ophüls, a professor at

Stanford University Hospital (San Francisco), discoverer. that the causative agent of the disease that

was at first called Coccidioides infection and later

coccidioidomycosis[58] was

a fungal pathogen, and coccidioidomycosis was also distinguished from Histoplasmosis and Blastomycosis.

Further, Coccidioides immitis was identified as the culprit of

respiratory disorders previously called San Joaquin Valley fever, desert fever,

and Valley fever, and a serum precipitin test was developed by Charles E. Smith

that was able to detect an acute form of the infection. In retrospect, Smith

played a major role in both medical research and raising awareness about

coccidioidomycosis,[59] especially

when he became dean of the School of Public Health at the University of

California at Berkeley in 1951.

Coccidioides immitis was

considered by the United States during the 1950s and 1960s as a potential

biological weapon.

The

strain selected for investigation was designated with the military symbol OC,

and initial expectations were for its deployment as a human incapacitant.

Medical research suggested that OC might have had some lethal effects on the

populace, and Coccidioides immitis started to be classified by

the authorities as a threat to public health. However, Coccidioides

immitis was never weaponized to the public's knowledge, and most of

the military research in the mid-1960s was concentrated on developing a human

vaccine.[

Currently, it is not on the U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services' or Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention's list

of select

agents and toxins.

In 2002, Coccidioides posadasii was

identified as genetically distinct from Coccidioides immitis despite

their morphologic similarities and can also cause coccidioidomycosis.

Research

As of 2013, there is no vaccine available to prevent infection with Coccidioides immitis or Coccidioides posadasii, but efforts to develop such a vaccine are underway.

A dog with

coccidioidomycosis.

Valley fever is not contagious.

In dogs, the most common symptom of

coccidioidomycosis is a chronic cough, which can be dry or moist. Other

symptoms include fever (in approximately 50% of cases), weight loss, anorexia,

lethargy, and depression. The disease can disseminate throughout

the dog's body, most commonly causing osteomyelitis (infection

of the bone), which leads to lameness. Dissemination can cause other symptoms,

depending on which organs are infected. If the fungus infects the heart

or pericardium,

it can cause heart

failure and death.

In cats, symptoms may include skin

lesions, fever, and loss of appetite, with skin lesions being the most common.

Other species in which Valley fever has

been found include livestock such as cattle and horses; llamas; marine mammals,

including sea otters; zoo animals such as monkeys and apes, kangaroos, tigers,

etc.; and wildlife native to the geographic area where the fungus is found,

such as cougars, skunks, and javelinas.

In

Popular Culture

·

In the Season 1 episode of Bones called

"The Man in the

Fallout Shelter" the

entire lab is exposed to coccidioidomycosis through inhalation of bone dust.

Erroneously, the team is forced to quarantine in the lab on Christmas Eve to

prevent the disease from spreading to the public (in real life, the disease is

not contagious).

o

The lab is later exposed to it agai

o

n in the Season 2 episode "The Priest in

the Churchyard" from

contaminated graveyard soil but only receives a series of injections rather

than be forced to quarantine.[70]

·

Everything in Between,

a 2022 Australian feature film, contains references to coccidioidomycosis.

·

In Doctor House, season 3 episode 4

"Line in the Sand", a 17 years old patient has a Coccidioides

infection.

Jan Ricks Jennings, MHA, LFACHE

Senior

Consultant

Senior

Management Resources, LLC

JanJenningsBlog.Blogspot.com

February

12, 2023

No comments:

Post a Comment