Cryptococcal disease

😊

Cryptococcus gattii, formerly known as Cryptococcus

neoformans var. gattii, is an encapsulated yeast found primarily in tropical and subtropical climates. Its teleomorph is Filobasidiella

bacillispora, a filamentous fungus belonging to

the class Tremellomycetes.

Cryptococcus gattii causes the

human diseases of pulmonary cryptococcosis (lung

infection), basal meningitis, and cerebral cryptococcomas.

Occasionally, the fungus is associated with skin, soft tissue, lymph node, bone, and joint infections. In

recent years, it has appeared in British Columbia, Canada and the Pacific Northwest.[1] It has been suggested[2][3] that global warming may have been

a factor in its emergence in British Columbia. It has also been suggested

that tsunamis, such as the 1964 Alaska earthquake and tsunami,

might have been responsible for carrying the fungus to North America and its

subsequent spread there.[4] From 1999 through to early

2008, 216 people in British Columbia have been infected with C. gattii,

and eight died from complications related to it.[5] The fungus also infects

animals, such as dogs, koalas, and dolphins.[3] In 2007, the fungus appeared

for the first time in the United States, in Whatcom County,

Washington[6] and in April 2010 had spread to

Oregon.[7] The most recently identified

strain, designated VGIIc, is particularly virulent, having proved fatal in 19

of 218 known cases.[8]

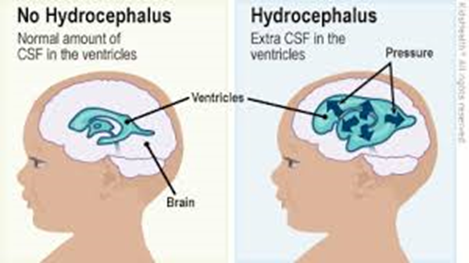

Cryptococcal

disease is a very rare disease that can affect the lungs (pneumonia) and nervous system (causing

meningitis and focal brain lesions called cryptococcomas) in humans. The main

complication of lung infection is respiratory failure. Central nervous system

infection may lead to hydrocephalus, seizures, and

focal neurological deficit.

Soil debris

associated with certain tree species has been found frequently to contain C.

gattii and less commonly VGI MATα, in Southern California. These

isolates were fertile, were found to be indistinguishable from the human

isolates by genome sequence were virulent in in vitro and

animal tests. Isolates were found associated with Canary Island, American, and

Pohutukawa tree Leading up to the study one of the authors, Scott Filler,

sent his daughter Elan to obtain and culture fungal samples in the greater Los

Angeles area; one of these turned out to be C. gattii.[11] Her work was presented at the

Los Angeles County Science Fair, and she was credited as an author on the

publication.[12]

Lead author Deborah

Springer said, "Just as people who travel to South America are told to be

careful about drinking the water, people who visit other areas like California,

the Pacific Northwest, and Oregon need to be aware that they are at risk for

developing a fungal infection, especially if their immune system is

compromised."[13]

Epidemiology

The highest

incidences of C. gattii infections occur in Papua New Guinea

and Northern Australia. Cases have also been reported in other regions,

indicating its spread to India, Brazil, Vancouver Island in Canada, and

Washington, and Oregon in the United States.

Unlike is not

particularly associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection or other

forms of immunosuppression. The fungus can cause disease in healthy people,

potentially due to its ability to grow extremely rapidly within white blood

cells.[14]

In the United

States, C. gattii serotype B, subtype VGIIa, is largely

responsible for clinical cases. The VGIIa subtype was responsible for the

outbreaks in Canada; it then appeared in the U.S. Pacific Northwest.

According to a CDC

summary, from 2004 to 2010, 60 cases were identified in the U.S.: 43 in Oregon,

15 from Washington, and one each from Idaho and California. Slightly more than

half of these case were immunocompromised; 92% of all isolates were of the

VGIIa subtype. In 2007, the first case in North Carolina was reported, subtype

VGI, which is identical to the isolates found in Australia and California. In

2009, one case was identified in Arkansas.

The multiple clonal

clusters in the Pacific Northwest likely arose independently of each other as a

result of sexual reproduction occurring

within the highly sexual VGII population.[15] VGII C. gattii have

probably undergone either bisexual or unisexual reproduction in multiple

different locales, thus giving rise to novel virulent phenotypes.

Transmission

The infection is caused by inhaling yeasts or spores. The fungus is not transmitted from person to person or from animal to person. A person with cryptococcal disease is not contagious.

Symptoms

Most people who are

exposed to the fungus do not become ill. In people who become ill, symptoms

appear many weeks to months after exposure. Symptoms of cryptococcal disease

include:

·

Prolonged cough (lasting weeks or months)

·

Sputum production

·

Sharp chest pain

·

Shortness of breath

·

Sinusitis (cottony drainage, soreness, pressure)

·

Severe headache (meningitis, encephalitis, meningoencephalitis)

·

Stiff neck (prolonged and severe nuchal rigidity)

·

Muscle soreness (mild to severe, local or diffuse)

·

Photophobia (excessive sensitivity to light)

·

Blurred or double vision

·

Eye irritation (soreness, redness)

·

Focal neurological deficit

·

Fever (delirium, hallucinations)

·

Confusion (abnormal behavior changes, inappropriate mood swings)

·

Seizures

·

Dizziness

·

Weight loss

·

Nausea (with or without vomiting)

·

Skin lesions (rashes, scaling, plaques, papules, nodules,

blisters, subcutaneous tumors or ulcers)

·

Lethargy

·

Apathy

Diagnosis

Culture of sputum,

bronchoalveolar lavage, lung biopsy, cerebrospinal fluid or brain biopsy

specimens on selective agar allows differentiation between the five members of

the C. gattii species complex and the two members of the C.

neoformans species complex.

Molecular

techniques may be used to speciate Cryptococcus from specimens

that fail to culture.

Cryptococcal

antigen testing from serum or cerebrospinal fluid is a useful preliminary test

for cryptococcal infection and has high sensitivity for disease. It does not

distinguish between different species of Cryptococcus.

Treatment

Medical treatment

consists of prolonged intravenous therapy (for 6–8 weeks or

longer) with the antifungal drug amphotericin B, either in its

conventional or lipid formulation. The addition of oral or intravenous flucytosine improves response rates.

Oral fluconazole is then administered for six

months or more.

Antifungals alone

are often insufficient to cure C. gattii infections, and

surgery to resect infected lung (lobectomy) or brain is often required. Ventricular shunts and Ommaya reservoirs are sometimes

employed in the treatment of central nervous system infection.

People who

have C. gattii infection need to take prescription antifungal

medication for at least 6 months; usually the type of treatment depends on the

severity of the infection and the parts of the body that are affected.

·

For people who have asymptomatic infections or

mild-to-moderate pulmonary infections, the treatment is usually fluconazole.

· For people who have severe lung infections, or infections in the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord), the treatment is amphotericin B in combination with flucytosine.

Jan Ricks Jennings, MHA,

LFACHE

Senior Consultant

Senior Management Services

Senior Management Resources,

LLC

Jan,Jennings@EagleTalon.net

JanJenningBlog.Blogspot.com

412,913.0636 Cell

724.733.0509 Office

No comments:

Post a Comment